Here is my highly-selective Top 5 of the best feature writing to have come out of America. A ridiculous idea, I know. From Norman Mailer to David Foster Wallace, here are the US journalists who have certainly influenced me.

Here is my highly-selective Top 5 of the best feature writing to have come out of America. A ridiculous idea, I know. From Norman Mailer to David Foster Wallace, here are the US journalists who have certainly influenced me.

To my mind, the apogee of art is where fiction and non-fiction meet, twisted around each other like a strand of DNA. Look at how a TV show like The Affair uses a hand-held camera to give it a more fly-on-the-wall approach. Or a gripping cop show like the BBC’s The Line of Duty has a documentary feel.

Authors such as Ernest Hemingway and Scott Fitzgerald were really writing autobiography, whether it was Hemingway’s First World War experience in A Farewell to Arms or Fitzgerald coldly noting down what his wife Zelda said woozy with anaesthetic after the birth of their daughter Scottie for The Great Gatsby (“I hope she’ll be a fool — that’s the best thing a girl can be in this world, a beautiful little fool…”)

What is now called narrative non-fiction or “new journalism” took off in the Sixties, and we have become so used to it in magazines and feature articles, we don’t notice it anymore. It is important to remember that even in the early Sixties feature pages as we know them didn’t exist — in Britain newspapers such as the one I work for, The Daily Telegraph, baldly stated the news which consisted of eight flimsy (rationed) pages. It was down to magazine writers like Tom Wolfe and Gay Talese in New York to invent the form.

Today, in a magazine world where PRs get to approve copy in exchange for access to Hollywood stars, it is hard to imagine a journo like Talese being given unfettered roaming rights to a star like Sinatra and being allowed to write whatever he wants. Today’s “in-depth” magazine profiles often consist of a trawl through the cuttings and 20 minutes with a star in a junket hotel bedroom, watched over by a disapproving PR. And I am as guilty as the rest of them.

Here are five pieces of narrative non-fiction that you must read:*

Some Dreamers of the Golden Dream, Joan Didion

Didion, one of those writers with what Graham Greene called “a chip of ice in the heart”, recounts a true-life case in Sixties California as if it was a James M Cain murder novel with the hot and dusty Santa Ana winds driving a  wife to murder. “It is the season of suicide and divorce and prickly dread wherever the winds blow,” she writes. Didion is especially brilliant at metaphor, and has a killer final image — as the adulterous wife’s lover goes up the aisle for a second time, Didion details her wedding dress, ending with the words, “a coronet of seed pearls held her illusion veil.” (Slouching Towards Bethlehem, Zola Books, 2015)

wife to murder. “It is the season of suicide and divorce and prickly dread wherever the winds blow,” she writes. Didion is especially brilliant at metaphor, and has a killer final image — as the adulterous wife’s lover goes up the aisle for a second time, Didion details her wedding dress, ending with the words, “a coronet of seed pearls held her illusion veil.” (Slouching Towards Bethlehem, Zola Books, 2015)

The Muses Are Heard, Truman Capote

Capote was one of the first American writers to introduce fiction techniques into journalism. This 1956 piece for The New Yorker recounts a visit to Moscow by the Broadway cast of Porgy and Bess. Capote dizzyingly described himself as “a Semantic Paganini” and it is hard to argue against his almost perfect ear. The author went on to write the classic non-fiction novel In Cold Blood. (A Capote Reader, Penguin Classics, 2002)

techniques into journalism. This 1956 piece for The New Yorker recounts a visit to Moscow by the Broadway cast of Porgy and Bess. Capote dizzyingly described himself as “a Semantic Paganini” and it is hard to argue against his almost perfect ear. The author went on to write the classic non-fiction novel In Cold Blood. (A Capote Reader, Penguin Classics, 2002)

Ten Thousand Words a Minute, Norman Mailer

After pooh-poohing what Truman Capote had done in In Cold Blood, Mailer embraced the concept wholeheartedly writing a string of brilliant non-fiction books including the Pulitzer Prize-winning  The Executioner’s Song. Poet Robert Lowell called him the greatest journalist in America (“I thought I was the greatest novelist in America,” the pugnacious Mailer replied). This 1962 magazine piece for Esquire has some of the best prose I have ever read, as Mailer describes the moment when boxer Emile Griffith kills his opponent in the ring: “Some part of his death reached out to us. One felt it hover in the air. He was still standing in the ropes, trapped as he had been before, he gave some little half-smile of regret, as if he was saying, ‘I didn’t know I was going to die just yet,’ and then, his head, leaning back but still erect, his death came to breathe about him, and he sank slowly to the floor. He went down more slowly than any fighter had ever gone down, he went down like a large ship that turns on end and slides second by second into its grave. As he went down, the sound of Griffith’s punches echoed in the mind like a heavy ax in the distance chopping into a wet log.” If that isn’t exciting writing, I don’t know what is. (The Time of Our Time, Abacus 1999)

The Executioner’s Song. Poet Robert Lowell called him the greatest journalist in America (“I thought I was the greatest novelist in America,” the pugnacious Mailer replied). This 1962 magazine piece for Esquire has some of the best prose I have ever read, as Mailer describes the moment when boxer Emile Griffith kills his opponent in the ring: “Some part of his death reached out to us. One felt it hover in the air. He was still standing in the ropes, trapped as he had been before, he gave some little half-smile of regret, as if he was saying, ‘I didn’t know I was going to die just yet,’ and then, his head, leaning back but still erect, his death came to breathe about him, and he sank slowly to the floor. He went down more slowly than any fighter had ever gone down, he went down like a large ship that turns on end and slides second by second into its grave. As he went down, the sound of Griffith’s punches echoed in the mind like a heavy ax in the distance chopping into a wet log.” If that isn’t exciting writing, I don’t know what is. (The Time of Our Time, Abacus 1999)

War, Sebastian Junger

If you want to know what it’s like to be in the stinking furnace of Afghanistan with white-hot tracer bullets zipping past you, read this book. Junger spent a year living with a forward platoon of American soldiers in the  Korengal Valley, reputed to be the deadliest valley in Afghanistan. It gets you inside the mind of a US Marine, the ghostly exhaustion of a tour of duty and how the entire US Army acts as support for this tip of the spear. This book was pulled together from Vanity Fair articles — one of the last places which still does this long-form journalism — and also provided the basis for the Academy Award-nominated documentary Restrepo. (War, Fourth Estate 2010)

Korengal Valley, reputed to be the deadliest valley in Afghanistan. It gets you inside the mind of a US Marine, the ghostly exhaustion of a tour of duty and how the entire US Army acts as support for this tip of the spear. This book was pulled together from Vanity Fair articles — one of the last places which still does this long-form journalism — and also provided the basis for the Academy Award-nominated documentary Restrepo. (War, Fourth Estate 2010)

A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again, David Foster Wallace

Funny is money, as the show business saying goes, and David Foster Wallace’s account of a holiday cruise in the Caribbean had me shaking with laughter when I first read it. Being funny is difficult in print. It usually involves  using exclamation marks! which, to my mind, are like somebody putting on a red nose and doing jazz hands. Foster Wallace is hilarious throughout this account of a ghastly trip on one of those mid-level, all-inclusive cruises. Another of Foster Wallace’s pieces of reportage for Harper’s, A Visit to the Fair, made me laugh so much I thought I was going to be sick. (A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again, Abacus 2012)

using exclamation marks! which, to my mind, are like somebody putting on a red nose and doing jazz hands. Foster Wallace is hilarious throughout this account of a ghastly trip on one of those mid-level, all-inclusive cruises. Another of Foster Wallace’s pieces of reportage for Harper’s, A Visit to the Fair, made me laugh so much I thought I was going to be sick. (A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again, Abacus 2012)

*As the form originated in the States, I have restricted my selection to American writers — I would be grateful for any recommendations from France, Germany, Japan, etc.

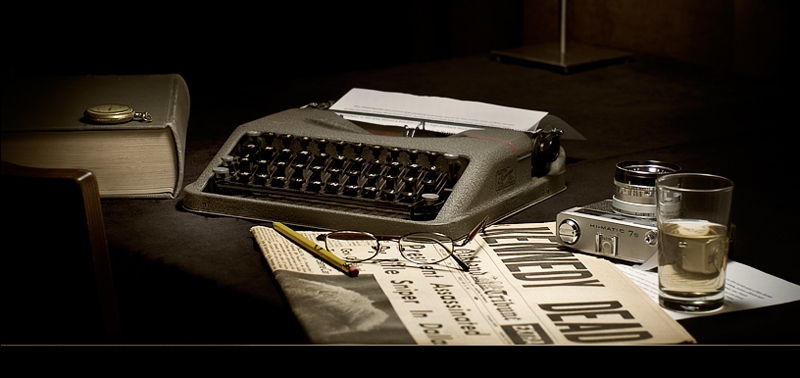

Reporter’s Desk, November 1963 Photograph: © Brian Watkins all rights reserved